성인 대상 정신건강 관리를 위한 생태순간중재 연구 전략: 주제범위 문헌고찰

Copyright ⓒ 2024 The Digital Contents Society

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-CommercialLicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

초록

최근 기술 향상에 따라 스마트폰 애플리케이션을 활용한 정신건강 증진 중재가 시도되고 있으며 그중 생태순간중재(EMI; ecological momentary intervention)은 대상자의 실생활에서 수집한 정보를 기반으로 대상자 중심의 중재가 가능하다는 장점이 있다. 본 연구에서는 EMI를 적용한 성인 대상 정신건강 증진 연구의 문헌고찰을 통해 현황을 분석하고 중재에 적용한 전략에 대해 알아보고자 한다. 문헌검색은 2017년 1월부터 2023년 1월까지 출판된 문헌을 대상으로 PubMed, CINAHL 및 EMBASE 데이터베이스를 사용하였다. 총 689개 연구가 검색되었고 최종적으로 총 10편의 연구를 분석하였다. 각 연구에서 중재 목적은 걱정 및 불안 감소, 주관적 웰빙 및 사회적지지, 회복탄력성 증진 등이 있었다. 마음챙김 명상 기반으로 수행된 연구가 총 8편이었고 연구목적으로 개발한 애플리케이션을 활용한 연구가 총 8편이 있었다. 중재 효과가 있었던 변수는 불안, 우울, 업무 긴장, 사회적지지, 주관적 웰빙이었다. 본 연구 결과를 통해 EMI 연구의 현황과 중재 전략을 확인할 수 있었다. 본 연구는 향후 성인 대상 정신건강 중재 및 애플리케이션 개발에 기초 자료로 활용될 수 있을 것이다.

Abstract

With recent improvements in technology, mental health promotion interventions have been attempted using applications, and such ecological momentary interventions(EMI) have the advantage of being patient-centered interventions based on data collected from participants’ real life. In this study, we conducted a literature review of adult mental health promotion studies using EMI to explore the strategies used in the PubMed, CINAHL, and EMBASE databases from January 2017 to January 2023. A total of 689 studies were retrieved and 10 studies were finally analyzed. In each study, the intervention goals were to reduce worry and anxiety, increase subjective well-being and social support, and promote resilience. The interventions included mindfulness-based interventions in seven studies and purposeful applications in eight studies. The intervention variables were anxiety, depression, work strain, social support, and subjective well-being. The results of this review confirm the EMI intervention strategies of existing studies and can be used to inform the future development of mental health interventions and applications for adults.

Keywords:

Mental Health, Ecological Momentary Intervention, Adult, Smartphone Application, Scoping Review키워드:

정신건강, 생태순간중재, 성인, 스마트폰 애플리케이션, 주제범위 문헌고찰Ⅰ. 서 론

1-1 연구의 필요성

정신건강(Mental health)은 공중보건에 있어서 중요하게 다루어지고 있는 건강 이슈이다[1],[2]. 국제보건기구(WHO; world health organization)에서는 정신건강을 개인의 잠재력을 실현하고 공동체에 유익하도록 기여하는 것으로 정의하며 지속 가능한 발전 목표(SDGs; Sustainable development goals)에 정신건강 증진을 포함시켰다[3]. 최근 급격한 현대화와 코로나19 팬데믹, 각종 재난, 사건, 사고 발생에 따라 국민들은 불안감, 두려움, 사회적 단절, 스트레스를 경험하며 정신건강에 어려움을 경험하고 있다. 이는 개인, 조직, 사회, 국가 건강에 영향을 줄 수 있으므로 중요하게 고려해야 할 필요성이 있다[4]. 2021년 국내 정신건강 실태조사에 따르면 일반인 중 약 25% 이상이 평생 한 번 이상 우울, 불안, 니코틴 사용 장애, 알코올 사용 장애를 경험하는 것으로 보고되었다[5]. 국내 자살률은 2020년 국민 10만 명당 25.7명으로 경제 협력 개발기구(OECD: Organization for economic cooperation and development) 회원 국가 중 자살률 1위를 기록하였다[6].

일반 국민 중 성인은 사회 및 경제 활동의 주축을 이루어 정신건강 관리가 중요하며 이를 위해서는 대학교, 직장을 포함한 지역사회에서 이루어질 수 있는 전문적 도움 및 정신건강 증진 프로그램 개발 및 운영이 필요하다. 현재 정신건강 관련 우울, 불안 등 어려움을 경험하는 대상자의 약 20% 가 전문적 도움을 받고 있어[7], 정신건강 자원의 활용이 낮은 상태이다. 이는 정신건강과 관련한 낙인효과, 시간과 비용의 부담이 작용한 것으로 볼 수 있다. 따라서 지역사회에서 일반 성인 대상자의 정신건강 어려움 예방 및 증진을 위한 낙인효과가 적고 접근이 쉬운 효과적인 중재 방법이 필요하다.

최근 보건의료 환경에서 정신건강 증진을 위해 디지털 테크놀로지 기술을 활용한 중재가 시도되고 있다[8]. 선행연구에 따르면 국내에서 수행된 정신건강 관련 스마트폰 애플리케이션을 활용한 연구는 총 2,777편으로 각 연구에서 적용한 중재 방법으로 교육 및 상담 등이 있었다[9]. 그중 생태순간중재(EMI; ecological momentary intervention)는 대상자의 실생활(real-world), 실시간(real-time) 정보를 기반으로 건강 관련 행동, 정서 등을 중재할 수 있으며 시간과 장소에 제한 없이 중재가 이루어져 비용 효과적이고 접근성이 좋다[7]. 대상자의 정서, 스트레스, 활동 등의 정보를 회상 편향(recall bias) 없이 정확하게 수집하는 생태순간평가(EMA: ecological momentary assessment)를 기반으로 하는 EMI는 대상자 증상 및 상황에 알맞은 대상자 중심의 중재를 제공할 수 있다[7]. EMI를 적용한 중재 관련 메타분석 연구에 따르면 불안장애 환자에게 불안 증상을 감소 및 스트레스 완화에 효과적이었고[8], 환각 증상이 있는 대상자에게 EMI 적용은 대상자의 자가 모니터링 및 증상 관리를 촉진하였다[8],[10]. Bell 등[10]의 연구에서 환각 증상이 있는 정신과 환자 대상으로 EMI를 적용하여 실생활에서 환각 증상 정보를 수집하였고, 수집된 정보를 기반으로 관리 및 피드백을 통해 대상자의 환각 증상 감소 및 대처 기술이 향상시켰다.

선행 문헌고찰 연구[7]에서는 알코올 중독자, 조현병 환자, 우울증 환자 등 정신과 환자를 중심으로 연구가 진행되어 일반인 대상 EMI 중재 연구 계획 시 근거 적용에 제한되었고 각 연구에 참여한 대상자 특성 및 연구설계, 이론, 개념에 대한 설명이 부족하였다. 최근 EMI 연구는 다양한 국가에서 이루어지고 있고[7],[8], 앞으로 국내에서 원격 의료 기술을 적용한 EMI 연구가 진행될 것을 예측했을 때 선행연구에서 적용된 연구설계 및 이론, 개념, 중재 전략에 대한 고찰이 필요하다.

주제범위 문헌고찰(scoping review) 연구 방법은 관심 주제에 대한 연구 정보를 광범위한 조사를 통해 연구 수행 정보를 확인할 수 있고, 연구 개념과 방법의 매핑(mapping)을 통해 향후 연구 방향에 대한 정보를 제공할 수 있다[11]-[13]. 이에 본 연구에서는 주제범위 문헌고찰 연구 방법으로 EMI를 적용한 성인 대상 정신건강 중재 연구를 고찰하여 연구 전략을 알아보고자 한다.

1-2 연구목적

본 연구의 목적은 국내, 외 문헌에서 일반 성인 대상 정신건강 증진을 위한 EMI를 적용한 연구의 현황 및 특성을 확인하고, 문헌에서 적용한 연구 전략을 파악하기 위함이다.

Ⅱ. 연구방법

2-1 연구설계

본 연구는 국내, 외 EMI를 적용한 연구를 대상으로 수행한 주제범위 문헌고찰이다. 주제범위 문헌고찰 결과는 근거기반 임상 실무, 연구 방향, 정책 방향 결정에 근거가 됨에 따라 다양한 연구 분야에 적용되고 있으며[11], 새롭게 출현하는 주제 및 내용 확인, 특정 분야에 대한 연구 현황을 파악하는데 도움이 된다. 본 연구에서는 Joanna Briggs Institute(JBI)의 가이드라인과 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR)[11]에 따라 주제범위 문헌고찰을 수행하였다.

2-2 연구절차

본 연구에서는 주제범위 문헌고찰 절차는 1. 연구 질문 설정, 2. 문헌 검색 및 선정, 3. 자료 추출 및 분석, 4. 결과보고 순으로 진행하였다.

본 연구에서는 연구 질문으로 1) 일반 성인 대상으로 지역사회에서 EMI를 적용한 정신건강 증진 연구의 일반적 특성 및 연구설계가 어떠한가? 2) 중재 연구에서 적용한 이론 또는 개념은 무엇인가? 3) 중재 전략은 무엇인가? 로 선정하였다.

본 연구의 문헌 선정 기준은 JBI에서 권고하는 방법에 따라 대상자(population), 개념(concept), 맥락(context)에 따라 설정하였다. 이에 따라 연구대상자는 질병이 없는 일반 성인 대상자, 개념은 EMI, 맥락은 지역사회로 정하였다.

본 연구에서는 최근 연구 동향을 살피기 위하여 2017년 1월부터 2023년 1월까지 최근 6년간 게재된 연구 논문을 분석하였다. 예비 검색 시 국내 저널에서 출판된 연구가 없었다. 이에 국내 데이터베이스 검색은 제외하였고, 국외 연구에서는 Pubmed, CINAHL, EMBASE 전자데이터 베이스에서 문헌을 검색하였다. 검색어 설정 시에는 생태순간중재 관련 선행연구[14, 15]에서 적용한 문헌고찰 키워드를 참고로 하였다. 일반 성인 대상 정신건강 관련 증상, 이슈로 보고되는 스트레스, 불안, 우울, 부담을 주 키워드로 정하였고[4, 5]. 실험연구 중 인과관계 가설 검정에 효과적인 무작위 시험설계(RCT: randomized controlled trials)를 키워드에 포함했다. 본 연구에서 검색 시 생태순간중재와 관련한 키워드인 “ecological momentary intervention”, 일반 성인 대상 정신건강 관련 키워드인 “stress”, anxiety”, “depression”, “burden” 등과 연구 방법인 RCT를 조합하였다(표 1).

본 연구에서는 다양한 근거를 검토하기 위해 문헌의 종류에 프로토콜 논문과 회색 문헌을 포함하였다.

본 연구에서는 각 연구의 저자, 게재 연도, 대상자, 중재 기간, 중재 방법, 중재 효과에 대해 자료 추출 후 분석하였다. 대상자 수의 경우 연구 초기 참여자를 기준으로 추출하였다. 연구 방법 설계 및 중재 전략의 분석은 기존의 연구 특성을 확인하고 추후 연구 방향에 대한 제안할 수 있다.

Ⅲ. 연구 결과

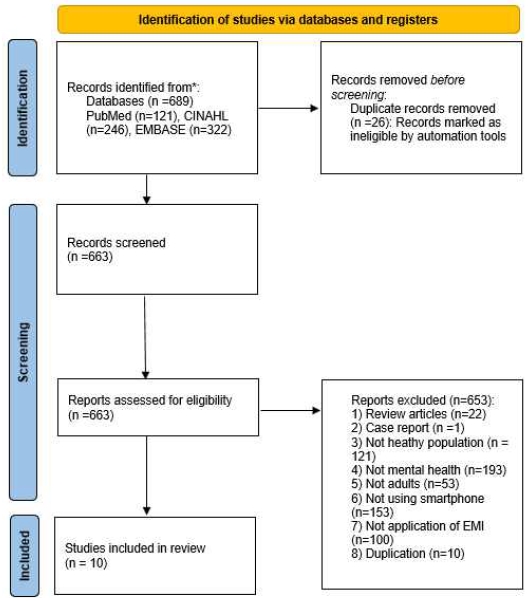

문헌검색 결과 총 689편이 검색되었고 중복되는 논문을 제거하여 총 663편의 논문의 제목과 초록을 검토하였다. 논문의 제목과 초록 확인하였고, 판단이 어려운 경우 원문 확인 및 타 연구자에게 검토를 의뢰하였다. 최종적으로 653편이 배제되었고, 배제 사유는 문헌고찰 논문 22편, 사례 연구 1편, 환자 대상 연구 121편, 정신건강 관련 주제가 아닌 연구가 193편, 성인 대상이 아닌 경우가 53편, 스마트폰을 사용하지 않은 연구가 153편, EMI를 적용하지 않은 연구 100편, 중복 연구 10편이 있었다. 배제 논문을 제외한 총 10편의 논문 중 유사 실험 연구가 1편이 있었으나 EMI 관련 다양한 연구를 분석하기 위해 분석 대상 연구로 포함하였고 최종적으로 총 10편의 문헌을 분석하였다[16]-[25](그림 1).

최근 6년 동안 연구가 수행된 국가와 각 연구 편수는 미국 4편[17],[20],[23],[25], 독일 2편[16],[22], 영국[18], 한국[19], 오스트레일리아[21], 스페인[24]이 각각 1편씩이 있었다.

연구 논문의 종류를 살펴봤을 때 3편은 프로토콜 논문이었고[20],[22],[24], 6편은 RCT 연구였다[16]-[18],[21],[23],[25]. 대상자는 일반인 대상이 6편[16],[17],[19],[21]-[23], 직장인 1편[18], 대학생 1편[25], 병원 근로자 1편[24], 의사 1편[20]이 있었다. 대상자 수는 최저 30명[19]에서 최고 2,134명[20]이었고 실험군의 대상자 수를 살펴봤을 때 1개 그룹당 17명이 가장 적었다[19]. 연구설계를 살펴봤을 때 중재군에서 EMI 효과, EMA 효과 각각 확인하는 연구가 총 2편이었다[19],[24]. Everitt 등[21]의 연구에서는 중재에 3개 그룹을 두어 EMI 효과, EMA 효과, 촉진 메시지 전송 효과를 살펴보는 연구를 수행하였다. Godara 등[22]의 연구에서는 실험군을 2개로 하여 1개의 그룹에서는 사회정서 훈련, 1개의 그룹은 마음챙김 명상을 적용한 중재를 계획하였다.

10편의 연구에서 대상자 연령대는 20대에서 40대였다. Rizvi 등[25]의 연구에서 대상자 평균 연령은 20.74세(SD=2.68)로 가장 낮았고, 해당 연구는 코로나19 팬데믹 상황에서 대학생 대상으로 수행된 연구였다[25]. 대상자의 성별 비율을 살펴봤을 때 7편 연구[16]-[18],[20],[21],[23],[25] 에서 남성보다 여성의 참여 비율이 높았다. Everitt 등[21]의 연구에서는 여성의 비율이 85.5%였고, NeCamp 등[20]의 연구에서 여성의 비율이 55.9%로 가장 낮았다.

각 연구에서 중재의 주요 목적은 걱정 감소, 불안 완화, 주관적 웰빙 증진, 사회적지지, 업무 긴장 완화, 정서 조절, 활동, 수면, 사회 활동 증진, 회복탄력성 증진이었다(표 2).

각 연구의 중재 방법을 살펴봤을 때 중재 개발 시에 사용한 이론 또는 개념은 마음챙김 명상이 8편으로 가장 많았고[16]-[18],[21]-[25], 그 외 연구는 2편이 있었다[19],[20]. 마음챙김 명상을 기반한 각 연구를 세부적으로 살펴봤을 때는 ‘호흡 명상, 바디 스캔, 알아차림, 현재 경험, 수용, 감정 알아차리기, 개방하기, 스트레스 자각하기, 감사하기’가 있었다. 각 연구에서 많이 사용된 중재 기법은 ‘호흡 명상’으로 이는 부정적 생각에서 벗어나 호흡에 주의를 두는 것을 의미하며 총 5편에서 적용되었다[16],[21]-[24]. ‘알아차림’은 현재 일어나고 있는 상황을 비 판단적으로 인식하는 것을 의미하며 총 4편에서 적용되었다[16],[17],[23],[25]. ‘바디 스캔’은 신체의 각 부분에 세세한 감각을 느끼는 것을 의미하며 총 3편의 연구에서 적용되었다[16],[21],[23]. ‘수용‘은 경험에 대해 비 판단적으로 받아들이는 것을 의미하며 총 4편에서 적용되었다[17],[18],[24],[25]. 마음챙김 명상 이외 중재 방법을 적용한 연구 중 Meinlschmidt 등[19]의 연구에서는 정서적 반응 이론에 기반한 내 수용성 민감도(interoceptive sensitivity) 감소, 명상, 감정에 따른 표정 연습, 이미지와 문장을 활용한 중재를 하였다[19]. NeCamp 등[20]의 연구에서는 참여자의 행동과 정서에 대한 자각을 유도하고 이에 따른 실시간 중재(just-in-time adaptive interventions)를 통해 행동, 정서 변화를 살펴보았다.

중재를 전달하는 방법으로 비디오 및 오디오 콘텐츠를 활용한 중재는 총 9편이 있었다[16]-[19],[21]-[25]. Necamp 등[20]의 연구에서는 애플리케이션 알림 기능을 통해 정서, 수면, 신체활동에 대한 중재 메시지를 보냈다.

중재에 사용한 애플리케이션의 경우 8편의 연구에서 자체 개발하였고[16],[17],[19]-[22],[24],[25], 2편의 연구에서는 상용화된 애플리케이션을 활용하여 연구하였다[18],[23]. 중재 기간은 최소 10일[23]부터 최대 6달[20]이었고 평균적으로는 49.6일(SD=47.9)이었다.

EMA 횟수는 1일 기준으로 했을 때 최소 1일당 1회[19],[20],[24] 부터 최대 1일 5회[16]까지 있었다. Lindsay 등[17], Godara 등[22] 연구에서는 중재 전, 후 각각 불안, 정서를 측정하였고 중재 기간에는 측정하지 않았다. Bostock 등[18]의 연구에서는 중재 초기, 중기, 후기 3회 정서를 측정하였다.

프로토콜 논문을 제외한 8편의 연구에서 중재 결과를 살펴봤을 때 각 연구에서 종속변수로 살펴본 변수 중 효과가 있었던 연구는 총 7편이 있었다[17],[18]-[21],[23],[25]. 중재 효과가 있었던 변수로는 정서[16],[18],[20],[23],[25], 업무 긴장 및 업무 조절[18], 사회적지지[18], 외로움 및 사회적 상호작용[17], 주관적 웰빙[18], 불안[18],[21], 수면 및 활동[20], 우울[21], 부정적 생각[20] 이었다(표 3).

Ⅳ. 고 찰

본 연구는 최근 6년간 국내, 외 학술지에 게재된 일반 성인대상의 정신건강 관련 EMI 연구 특성을 분석하였다. 이를 통해 국내, 외 EMI 연구에서 사용한 연구설계, 방법, 중재 전략 등을 분석함으로써 향후 EMI 프로그램 개발에 근거를 마련하고자 하였다.

문헌검색 결과 국내 학술지에서 보고된 EMI 적용 연구는 없었고, 국외 학술지에 게재된 국내에서 수행한 연구도 1편으로 부족하였다. 선행연구에서는 국내 정신건강 관리를 위한 애플리케이션 적용 중재 연구가 4,000편 이상으로 보고되었고 각 연구에서 챗봇, 자가 증상기록, 교육 및 게임, 상담 피드백이 있었다[9]. 선행연구를 고려했을 때 국내에서 출판된 연구에서 자가 증상기록과 같이 EMI를 일부 적용한 연구는 있었으나 주요 중재 기법을 EMI로 적용한 연구는 없었다고 할 수 있다.

연구가 수행된 국가를 살펴봤을 때 국외에서는 미국, 캐나다, 독일과 같은 선진국에서 주로 이루어졌다. EMI 적용 연구는 인터넷 기반으로 애플리케이션 개발 및 활용이 유리한 국가에서 이루어질 수 있어서 연구환경을 반영한 결과라고 할 수 있다.

연구설계를 살펴봤을 때 실험군을 2개 그룹으로 설정하여 EMI와 EMA 효과를 비교하여 검증한 연구가 3편이 있었다[16],[21],[24]. 정신건강에 있어서 EMA 적용은 실생활에서 반복적으로 대상자의 정서, 스트레스 정도와 맥락 정보를 보고하므로 대상자가 자가 모니터링을 할 수 있어[26],[27], EMA 적용으로도 대상자의 정서 관리에 효과가 있다. EMI의 경우 EMA의 연장이라고 할 수 있으며 EMI는 EMA보다 더 적극적으로 대상자에게 일상생활에서 필요한 관리를 제공할 수 있다[26],[28]. 따라서 일부 분석 대상 연구에서 EMA, EMI 효과를 각각 검증하기 위해 실험군을 2개로 설정했다고 할 수 있다.

각 문헌에서 활용한 중재 기법은 마음챙김 명상을 기반으로 구성한 연구가 8편으로 가장 많았으며, 이는 EMI와 관련하여 체계적 문헌고찰 연구 결과와 유사하였다[14],[26]. 마음챙김 명상은 정서적, 인지적 메커니즘의 수정을 통해 불쾌한 감각, 어려운 생각, 불편한 감정을 줄일 수 있어 정신과 환자, 만성 질환자 및 일반인에게 광범위하게 적용할 수 있다[29],[30]. 성인 대상 마음챙김 명상이 효과적이라는 보고가 있었고[31], 애플리케이션을 활용한 심리치료에 있어서 마음챙김 명상이 효과적이었다[32]. 각 EMI 연구에서는 마음챙김 명상의 장점인 시간과 장소에 제한 없이 대상자 스스로 현재에 집중하여 마음을 관리할 수 있다는 점을[29],[30] 반영했다고 할 수 있다.

분석 대상 총 9편 연구에서는 애플리케이션을 통한 비디오 및 오디오 콘텐츠를 제공하는 것이었고, 그중 3편의 연구에서는 애플리케이션 상에서 메시지를 통해 대상자의 일상생활에서 중재를 시도했다[20],[21],[24]. 총 10편의 연구에서 대상자의 현재 정서 상태를 EMA로 측정한 방법은 설문 방법이었고 1편의 연구에서는 정서 상태 측정과 함께 스트레스에 대한 마커로 24시간 동안의 심장 박동수의 변화를 측정하였다[16].

EMI 단계는 낮은 단계(Low-level)부터 높은 단계(High-level)까지 중재하는 방법이 다양하다[8]. 낮은 단계의 EMI 적용은 대상자에게 필요한 정보를 즉시 제공하는 것이고 높은 단계 EMI 적용은 대상자에게 수집한 실생활 데이터를 기반으로 패턴 분석 후 대상자와 중재자의 상호 작용 및 개별화된 맞춤형 중재를 제공하는 것이다[8]. 따라서 기존 연구에서는 실시간 패턴 분석 후 중재를 제공하는 연구는 없었으므로 EMI 단계를 낮은 단계에서 중간 단계 정도로 적용했다고 할 수 있다.

선행연구에서는 정신건강 관련 EMI 연구에서 활동 센서를 통해 대상자의 활동 및 중재 효과를 측정하였다[8],[14]. 본 분석 대상 연구에서 대상자 데이터 및 중재 효과 측정에 활동 센서를 적용한 연구는 없었다. 이는 연구대상자가 일반인이었고 이들이 심각한 우울 및 불안 증상으로 인한 사회적, 물리적 활동에 제한이 없어 각 연구에서 센서를 활용한 효과 측정을 하지 않았다고 할 수 있다.

중재에서 사용한 애플리케이션은 총 8편의 경우 연구를 위해 개발되었고, 2편의 연구에서는 기존 상용화된 애플리케이션을 활용하였다. 이는 각 연구의 목적과 대상, 사용 언어의 차이로 인하여 연구에서 자체적으로 애플리케이션을 개발했고, 기존 애플리케이션 활용한 연구의 경우 중재 내용 및 콘텐츠의 타당성과 안정성 검증을 통해 해당 연구에 적용한 것으로 설명할 수 있다. 최근에는 건강 관련한 다양한 애플리케이션이 개발되어 있다[9]. 기존에 개발된 애플리케이션 활용을 통해 재검증하여 비용 효과적인 연구가 진행될 필요성이 있다. 또한 애플리케이션 부분에서 나아가 대상자에게 중재 전달 방법에 대한 다양한 시도가 이루어질 필요성이 있다.

본 연구를 통해 EMI 연구의 연구설계, 중재 기법의 특성 및 효과를 알 수 있었다. EMI 적용은 일반 성인 대상 정신건강 중재에 가능하였고 정서, 업무 긴장 및 업무 조절, 사회적지지, 외로움, 사회적 상호작용, 주관적 웰빙, 불안, 수면 및 활동, 우울, 부정적 생각에 효과적이었다. 따라서 중재 효과가 있었던 변수를 고려하여 EMI 연구가 시도될 필요성이 있다. 최근에는 웨어러블 디지털 기술이 다양하게 개발되어[33] 향후 연구에서는 발전된 기술을 활용하여 대상자의 정보를 수집 및 중재 효과를 측정하는 연구가 시도될 필요성이 있다.

본 연구의 제한점은 문헌의 질 평가를 하지 않았다는 점에서 각 연구의 설계, 결과 보고에 대한 내적 타당도 확보에 제한이 있다는 것이다. 또한 연구 시작 전 주제범위 문헌고찰 프로토콜 등록을 하지 않고 진행했다는 점이다. 따라서 추후 연구에서는 연구의 질 평가 및 프로토콜 등록을 통해 문헌고찰 연구의 내적타당성 및 완결성을 높일 필요성이 있다. 또한 EMI에서 가장 많이 적용된 마음챙김 명상 내용의 세부적 방법, 효과 분석이 필요하다.

본 연구는 EMI 관련한 국문으로 발표된 연구로서, 애플리케이션을 활용한 정신건강 관련 EMI 적용의 현황과 방법을 분석하여 중재 전략에 대한 근거를 제공했다는 점에서 의의가 있다. 또한 앞으로 국내 정신건강 중재의 새로운 방향성을 제시했다. 본 연구는 향후 정신건강 중재 및 애플리케이션 개발에 기초 자료로 활용될 것이다.

Ⅴ. 결 론

본 연구는 최근 6년 동안 국내, 외 연구에서 출판된 일반성인 대상의 EMI를 적용한 정신건강 중재 연구의 일반적 특성과 중재 전략을 확인하였다. 국내에서 출판된 연구는 없었고 선진국 위주로 연구가 진행되었으며 주로 사용한 중재 개념에는 마음챙김 명상이었다. 중재 결과는 정서 관리, 불안, 스트레스 감소 등에 효과적임을 알 수 있었다. 앞으로 일반 성인의 정신건강 향상을 위해 일상생활에 적합하고 효과적 중재 프로그램이 필요하다. 이에 EMI의 장점을 활용하여 체계적인 중재가 이루어질 수 있도록 프로그램 개발을 해야 할 것이다. 또한 프로그램의 효과를 평가할 수 있는 다양한 기술 개발을 통해 연구 방법론의 발전을 기대한다.

Acknowledgments

이 성과는 정부(과학기술정보통신부)의 재원으로 한국연구재단의 지원을 받아 수행된 연구임(No. 2022R1G1A10091 32).

References

-

J. Campion, “Public Mental Health: Key Challenges and Opportunities,” BJPsych International, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 51-54, August 2018.

[https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2017.11]

-

J. Dykxhoorn, L. Fischer, B. Bayliss, C. Brayne, L. Crosby, B. Galvin, ... and K. Walters, “Conceptualising Public Mental Health: Development of a Conceptual Framework for Public Mental Health,” BMC Public Health, Vol. 22, 1407, July 2022.

[https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13775-9]

-

B. Saraceno and J. M. C. de Almeida, “An Outstanding Message of Hope: The WHO World Mental Health Report 2022,” Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, Vol. 31, e53, 2022.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000373]

-

N. Drissi, S. Ouhbi, M. A. J. Idrissi, L. Fernandez-Luque, and M. Ghogho, “Connected Mental Health: Systematic Mapping Study,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, Vol. 22, No. 8, e19950, August 2020.

[https://doi.org/10.2196/19950]

- National Center for Mental Health. National Mental Health Survey 2021 [Internet]. Available: https://mhs.ncmh.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301000000&bid=0005&act=view&list_no=16, .

-

H. A. Ji, S. R. Kim, M. S. Lee, S. H. Park, Y. S. Kim, K. H. Lee, and J. Y. Jun, “The Comparative Analysis of Mental Health Literacy in General Population: The Analysis of National Mental Health Literacy and Attitude Survey in 2021,” Korean Journal of Psychosomatic Medicine, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 38-45, June 2022.

[https://doi.org/10.22722/KJPM.2022.30.1.38]

-

A. Balaskas, S. M. Schueller, A. L. Cox, and G. Doherty, “Ecological Momentary Interventions for Mental Health: A Scoping Review,” PLoS ONE, Vol. 16, No. 3, e0248152, March 2021.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248152]

-

B. L. Gee, K. M. Griffiths, and A. Gulliver, “Effectiveness of Mobile Technologies Delivering Ecological Momentary Interventions for Stress and Anxiety: A Systematic Review,” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 221-229, January 2016.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocv043]

-

J. Lee and H. Choi, “Effects of Using Mobile Apps for Mental Health Care in Korea: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Korean Academy of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 88-100, March 2022.

[https://doi.org/10.12934/jkpmhn.2022.31.1.88]

-

I. H. Bell, S. F. Fielding-Smith, M. Hayward, S. L. Rossell, M. H. Lim, J. Farhall, and N. Thomas, “Smartphone-based Ecological Momentary Assessment and Intervention in a Blended Coping-Focused Therapy for Distressing Voices: Development and Case Illustration,” Internet Interventions, Vol. 14, pp. 18-25, December 2018.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2018.11.001]

-

M. D. J. Peters, C. Marnie, H. Colquhoun, C. M. Garritty, S. Hempel, T. Horsley, ... and A. C. Tricco, “Scoping Reviews: Reinforcing and Advancing the Methodology and Application,” Systematic Reviews, Vol. 10, 263, October 2021.

[https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3]

-

H. J. Seo, “The Scoping Review Approach to Synthesize Nursing Research Evidence,” Korean Journal of Adult Nursing, Vol. 32, No. 5, pp. 433-439, October 2020.

[https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2020.32.5.433]

-

S. Anderson, P. Allen, S. Peckham, and N. Goodwin, “Asking the Right Questions: Scoping Studies in the Commissioning of Research on the Organisation and Delivery of Health Services,” Health Research Policy and Systems, Vol. 6, 7, July 2008.

[https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-6-7]

-

A. Versluis, B. Verkuil, P. Spinhoven, M. M. van der Ploeg, and J. F. Brosschot, “Changing Mental Health and Positive Psychological Well-Being Using Ecological Momentary Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, Vol. 18, No. 6, e152, June 2016.

[https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5642]

-

K. P. Dao, K. De Cocker, H. L. Tong, A. B. Kocaballi, C. Chow, and L. Laranjo, “Smartphone-Delivered Ecological Momentary Interventions Based on Ecological Momentary Assessments to Promote Health Behaviors: Systematic Review and Adapted Checklist for Reporting Ecological Momentary Assessment and Intervention Studies,” JMIR mHealth and uHealth, Vol. 9, No. 11, e22890, November 2021.

[https://doi.org/10.2196/22890]

-

A. Versluis, B. Verkuil, P. Spinhoven, and J. F. Brosschot, “Effectiveness of a Smartphone-Based Worry-Reduction Training for Stress Reduction: A Randomized-Controlled Trial,” Psychology & Health, Vol. 33, No. 9, pp. 1079-1099, 2018.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2018.1456660]

-

E. K. Lindsay, S. Young, K. W. Brown, J. M. Smyth, and J. D. Creswell, “Mindfulness Training Reduces Loneliness and Increases Social Contact in a Randomized Controlled Trial,” PNAS, Vol. 116, No. 9, pp. 3488-3493, February 2019.

[https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1813588116]

-

S. Bostock, A. D. Crosswell, A. A. Prather, and A. Steptoe, “Mindfulness On-the-Go: Effects of a Mindfulness Meditation App on Work Stress and Well-Being,” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 127-138, 2019.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000118]

-

G. Meinlschmidt, M. Tegethoff, A. Belardi, E. Stalujanis, M. Oh, E. K. Jung, ... and J.-H. Lee, “Personalized Prediction of Smartphone-Based Psychotherapeutic Micro-Intervention Success Using Machine Learning,” Journal of Affective Disorders, Vol. 264, pp. 430-437, March 2020.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.071]

-

T. NeCamp, S. Sen, E. Frank, M. A.Walton, E. L. Ionides, Y. Fang, ... and Z. Wu, “Assessing Real-Time Moderation for Developing Adaptive Mobile Health Interventions for Medical Interns: Micro-Randomized Trial,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, Vol. 22, No. 3, e15033, March 2020.

[https://doi.org/10.2196/15033]

-

N. Everitt, J. Broadbent, B. Richardson, J. M. Smyth, K. Heron, S. Teague, and M. Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, “Exploring the Features of an App-Based Just-in-Time Intervention for Depression,” Journal of Affective Disorders, Vol. 291, pp. 279-287, August 2021.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.021]

-

M. Godara, S. Silveira, H. Matthäus, C. Heim, M. Voelkle, M. Hecht, ... and T. Singer, “Investigating Differential Effects of Socio-Emotional and Mindfulness-Based Online Interventions on Mental Health, Resilience and Social Capacities during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Study Protocol,” PLoS ONE, Vol. 16, No. 11, e0256323, November 2021.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256323]

-

J. W. Y. Kam, J. Javed, C. M. Hart, J. R. Andrews-Hanna, L. M. Tomfohr-Madsen, and C. Mills, “Daily Mindfulness Training Reduces Negative Impact of COVID-19 News Exposure on Affective Well-Being,” Psychological Research, Vol. 86, No. 4, pp. 1203-1214, June 2022.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-021-01550-1]

-

D. Castilla, M. V. Navarro-Haro, C. Suso-Ribera, A. Díaz-García, I. Zaragoza, and A. García-Palacios, “Ecological Momentary Intervention to Enhance Emotion Regulation in Healthcare Workers via Smartphone: A Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol,” BMC Psychiatry, Vol. 22, 164, March 2022.

[https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03800-x]

-

S. L. Rizvi, J. Finkelstein, A. Wacha-Montes, A. L. Yeager, A. K. Ruork, Q. Yin, ... and E. M. Kleiman, “Randomized Clinical Trial of a Brief, Scalable Intervention for Mental Health Sequelae in College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Behaviour Research and Therapy, Vol. 149, 104015, February 2022.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2021.104015]

-

I. H. Bell, M. H. Lim, S. L. Rossell, and N. Thomas, “Ecological Momentary Assessment and Intervention in the Treatment of Psychotic Disorders: A Systematic Review,” Psychiatric Services, Vol. 68, No. 11, pp. 1172-1181, November 2017.

[https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600523]

-

Y. S. Yang, G. W. Ryu, and M. Choi, “Methodological Strategies for Ecological Momentary Assessment to Evaluate Mood and Stress in Adult Patients Using Mobile Phones: Systematic Review,” JMIR mHealth and uHealth, Vol. 7, No. 4, e11215, April 2019.

[https://doi.org/10.2196/11215]

-

K. E. Heron and J. M. Smyth, “Ecological Momentary Interventions: Incorporating Mobile Technology Into Psychosocial and Health Behaviour Treatments,” British Journal of Health Psychology, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 1-39, February 2010.

[https://doi.org/10.1348/135910709x466063]

-

Z. Schuman-Olivier, M. Trombka, D. A. Lovas, J. A. Brewer, D. R. Vago, R. Gawande, ... and C. Fulwiler, “Mindfulness and Behavior Change,” Harvard Review of Psychiatry, Vol. 28, No. 6, pp. 371-394, November-December 2020.

[https://doi.org/10.1097/hrp.0000000000000277]

-

J. Wielgosz, S. B. Goldberg, T. R. A. Kral, J. D. Dunne, and R. J. Davidson, “Mindfulness Meditation and Psychopathology,” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 15, pp. 285-316, May 2019.

[https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093423]

-

S.-I. Yoon and H.-Y. Park, “Differential Effects of Mindfulness Meditation and Loving-kindness & Compassion Meditation on Prosociality and Antisociality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Korean Studies,” Korean Journal of Psychology: General, Vol. 42, No. 2, pp. 141-177, June 2023.

[https://doi.org/10.22257/kjp.2023.6.42.2.141]

-

N. Jeong and E. Kim, “Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis for Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Mindfulness-Based Mobile Application Psychotherapy for Depression,” Clinical Psychology in Korea: Research and Practice, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 1-29, March 2023.

[https://doi.org/10.15842/CPKJOURNAL.PUB.9.1.1]

-

J. S. Jang and S. H. Cho, “Mobile Health (m-health) on Mental Health,” Korean Journal of Stress Research, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 231-236, December 2016.

[https://doi.org/10.17547/kjsr.2016.24.4.231]

저자소개

2007년:국군간호사관학교(간호학 학사)

2017년:서울대학교 보건대학원(보건학 석사)

2021년:연세대학교 일반대학원(간호학 박사)

2017년 9월~2021년 8월: 연세대학교 간호대학 김모임 간호학 연구소 연구원

2021년 9월~2022년 2월: 남서울대학교 간호학과 조교수

2022년 3월~현 재: 한세대학교 간호학과 조교수

※관심분야:건강증진, 디지털헬스, 의료 빅데이터 등