Moderating Effects between Para-social Interaction and User Internal Factors on Live Streaming Commerce

Copyright ⓒ 2022 The Digital Contents Society

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-CommercialLicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the role of influencers' para-social interaction (PSI) and users' FoMO and involvement in the process of live commerce effect as digital marketing platform of companies, according to the increase of their industrial uses. An experiment was conducted to 127 college students. The results of ANOVA were as follows. First, PSI in live commerce was found to modulate attitudes toward live commerce(Alc) according to FoMO of consumers. Specifically, Alc was higher in the group with high FoMO at low PSI, but the group with low FoMO at high PSI was relatively high. Second, high PSI showed higher purchase intention than low PSI. Third, the group with low FoMO showed relatively higher Alc with high involvement products than with low-involvement. Overall, commerce with high PSI to low FoMO individual can increase the commerce attitude, and high PSI can increase the purchase intention.

초록

본 연구는 최근 실시간 라이브 스트리밍 기술의 산업적 활용이 증가함에 따라, 기업의 디지털 마케팅 플랫폼으로서 라이브커머스의 효과과정에 의사상호작용(PSI)과 이용자의 FoMO(포모) 및 관여가 조절역할을 하는지를 알아보는 것이다. 선행연구를 토대로 연구모형 설정과 라이브커머스 동영상을 이용한 설문조사를 실시하고 ANOVA 분석을 실시하였다. 분석결과는 첫째, 라이브 커머스에 대한 태도는 낮은 PSI에서는 FoMO가 높은 집단이 높았으나 높은 PSI에서는 FoMO가 낮은 집단이 상대적으로 높았다. 둘째, PSI가 높은 집단이 PSI가 낮은 집단보다 구매의도가 높게 나타났다. 셋째, FoMO가 낮은 집단에서 고관여 제품의 경우가 저관여 제품에 비해 라이브커머스 태도가 상대적으로 높게 나타났다. 전체적으로, 커머스 태도를 높이기 위해 개인의 FoMO가 낮고 인플루언서의 PSI가 높아야 하며, 구매의도를 높이기 위해서는 PSI 수준을 높이는 것이 유리함을 알 수 있다.

Keywords:

Live Streaming Commerce, Earned Media, Para-social Interaction(PSI), FoMO, Involvement키워드:

라이브 스트리밍 커머스, 획득매체, 의사상호작용, FoMO(포모), 관여Ⅰ. Introduction

Recently, live streaming technology attracts much attention by playing marketing role on commerce platform such as Naver and YouTube. Live commerce video can effectively deliver advertising messages due to the properties of digital broadcasting .[1]

In 2019, Amazon launched its own live commerce, and real-time live streaming offers a wealth of opportunities in advertising, consumer relationships and revenue. [2]. Such live commerce has explosive potential as an advertising medium by providing a realistic experience through interaction with consumers in reality.

For example, in the case of Naver, sellers can easily utilize live commerce through ‘live commerce tools’ such as real-time chatting with buyers, product tagging, URL sharing function, setting to receive news from the store, and push notifications before broadcasting. Through a relationship of trust with live commerce followers and subscribers, influencers can act as powerful persuasive or information sources providing product messages.[2]

Interacting with influencers on digital platforms is related to consumers' social motivation, that is, social connectedness. SNS(Social Network Service) helps people form online relationships, but on the other hand, it can increase psychological dependence on Internet, causing anxiety when ‘online’ is cut off, that is Fear of Missing Out (FoMO). FoMO is the fear of isolation experienced when the sense of connection through online is lost.[3][4] In this context, this study intends to examine the role of the fear of isolation factor, which is an important psychological factor of the individual and the interaction with the user, in the process of the influencer's persuasion effect.

Although the use of marketing using influencers is expanding, there is still a lack of academic approaches to demonstrate the effectiveness process in this regard. For example, by applying the concept of interaction between celebrities and ordinary people in traditional media to influencer marketing using social media, it is necessary to examine the influence on the attitudes and purchase intention of influencers toward products recommended by them. In this study, influencers were defined as ordinary people who are active online, excluding existing entertainers. This study is expected to provide theoretical and practical implications for influence marketing based on digital platforms such as review content and live commerce on social media.

Ⅱ. Theoretical Background

2-1 Live Streaming Formats as Marketing

Many studies have suggested that the reliability and favorability of influencers of influencers in live commerce are important factors.[5] The definition of an influencer is an independent third-party product guarantor who influences the attitude of a target audience through social media such as ‘blogs’ and tweets.[5] An influencer is a kind of guarantor who tells the public about a product or brand. However, instead of appearing in general commercial advertisements, influencers provide positive messages about products through social media such as Instagram or blogs.[6] In this regard, they can be said to provide advertisements in which a paid medium and an earned medium are combined. In addition, these influencers play a role in inducing word of mouth through YouTube, etc. Members or followers share with each other by adding their opinions to the opinions provided by influencers.

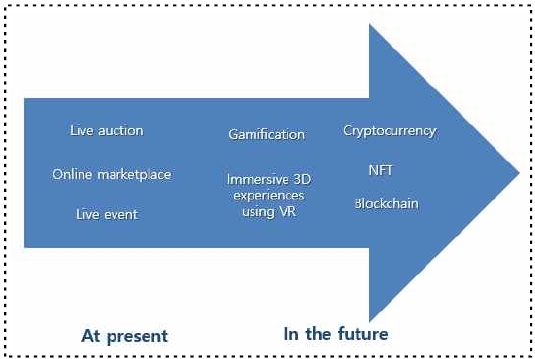

The growing influence of influencers has to do with how influencers interact with viewers through their broadcast content. It is said that watching the broadcast of influencers, viewers consume stories about the product, gain vicarious satisfaction and form positive emotions about the product.[7] Influencer interaction plays an important role in this process. This process can be realized through various formats of live streaming commerce such as online marketplaces, live auctions, live events, cryptocurrency and NFT being progressed now and in the future as shown in [Figure 1]. [20]

The interaction such as a timely response to consumer's reaction is a characteristic that is only possible in a digital media environment. For example, in the case of live commerce, by exchanging personalized messages using a digital environment such as mobile, users' content immersion may increase and may affect purchase intentions.

At the same time, one of the factors influencing the interaction process with users is FoMO as a user's individual social motive. People often click and watch live commerce out of fear that they will not be able to buy new products and fear that they will be alienated if they do not engage in social media activities.[8] This study focuses on the advertising effect of influencers' broadcasts in social media as a way for products to meet customers, and examines the relationship among influencer, user interaction, formo and involvement.

2-2 Para-social Interaction(PSI)

Para-social Interaction (PSI) refers to immersion or intervention that occurs when users have the illusion that they are talking with actors while consuming media.[9] In the existing online shopping, consumers mostly shopped passively, but in influencer marketing based on social media, consumers visit the store and communicate with the seller in real time, such as actively shopping through chatting or consulting on actual purchase. purchase experience. Also, while traditional celebrities endorse their products to the general public, influencers tend to focus on specific audiences. The process of identification is also different. While envy identification occurs with celebrities, it tends to occur with influencers largely based on similarity.[10]

In live commerce, viewing on the go or relatively using content using a mobile device is highly likely to be used temporarily or accidentally. In addition, live commerce is not only a commerce activity, but also real-time interaction and entertainment or social functions can be performed. In particular, live commerce is a medium for active social interaction. The real-time broadcast of the show host based on the user's reaction evokes conversation and bonding among users, increasing PSI (para-social interaction).[11] In fact, the show host reads real-time comments and appears to be talking to viewers frequently during the broadcast. In addition, show hosts often show how they treat viewers like close friends, and how they treat viewers. These interactions are expected to have a significant impact on repurchase of live commerce broadcasting products.

2-3 FoMO

FoMO (Fear of Missing Out) was originally a marketing term, proposed by author Patrick McGinnis [12], and became popular in 2004 as an article suggested by Harvard Business School magazine, Havers.

FoMO is used as a major variable in social media to explain growing addictions, such as fear of missing out or being excluded, or 'someone else is actually doing something worthwhile that they haven't had, or a situation in which, although not accurately identified, it appears to be. vague anxiety about '.[13] For example, FoMO can lead to obsessive concerns that appropriate opportunities to participate in social interactions or new experiences, profitable investments, or satisfying consumption events may be missed. In other words, in the context of product purchase or consumption, FoMO can induce people to imagine how their choices could have been different, thereby creating fear of making the wrong consumption or making a wrong purchase decision.[14] This fear further increases or exaggerates the preference for fashionable products recommended by the media. Show hosts in live commerce can be more trustworthy or sympathetic when they promote awareness or introduce products through various social proofs. Therefore, FoMO felt by an individual can increase attitude toward and purchase intention toward live commerce advertisement products. Furthermore, if the advertisement product is a luxury product with the property of being publicly disclosed, FoMO will act more and increase the attitude toward the luxury product and purchase intention.

2-4 Involvement

Involvement refers to a consumer's perceived personal relevance or interest in an object in a specific situation.[15] In some studies that dealt with whether involvement affects the intrinsic properties of a product or the importance of an advertising model when purchasing a product, it is reported that the influence of peripheral cues in advertising decreases as the level of involvement increases.

The influence of influencers in consumers' purchasing decision-making process can also be found in the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM). According to the elaboration possibility model, when both the motivation for information processing and the ability to process information are high, the change in attitude toward the product is affected by the product's own attributes. The attitude toward the product is formed by simple information such as peripheral cues.[16] Involvement factors can also be applied to PSI with show hosts by digital media. In the case of complex decision-making with high involvement, consumers value the intrinsic properties of live commerce products, such as quality, price, and convenience, but in simple decision-making with low involvement, live commerce's relationship with the show host, that is, the influence of PSI could be more important.

2-5 Independent Variables

This study intends to investigate whether the linear influence relationship of traditional advertising effect variables will appear in the live commerce commercial effect process. In other words, attitude toward live commerce has a positive effect on attitude toward live commerce products, which is expected to have a positive effect on product purchase intention.

2-6 Hypothesis and Research Model

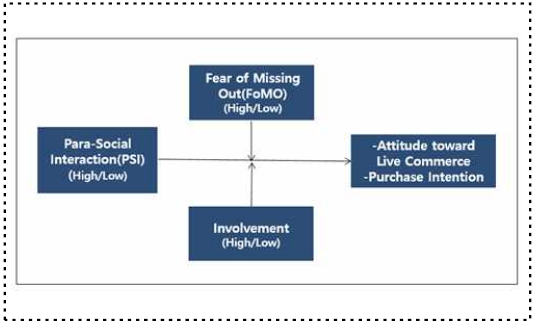

The effect of the PSI relationship between the live commerce show host (influencer) and the user (consumer) on attitude and purchase intention was investigated. To this end, referring to previous studies on the effects of show host and SNS advertisements, the relationship between PSI, FoMO, and involvement on the attitude toward live commerce and purchase intention was established as a hypothesis, and this was structured as shown in [Figure 2].

Hypothesis 1. The effectiveness of live commerce advertising will differ according to the PSI of the show host and user and the FoMO of the user.

Hypothesis 1-1. There will be a significant difference between the PSI (high/low) group and the FoMO (high/low) group with respect to live commerce attitudes.

Hypothesis 1-2. There will be a significant difference between the PSI (high/low) group and the FoMO (high/low) group for purchase intention.

Hypothesis 2. The effectiveness of live commerce advertisements according to FoMO will vary according to user involvement.

Hypothesis 2-1. There will be a significant difference between the FoMO (high/low) group and the engagement (high/low) group with respect to live commerce attitudes.

Hypothesis 2-2. There will be a significant difference between the PSI (high/low) group and the FoMO (high/low) group for purchase intention.

Ⅲ. Methods

3-1 Subjects

For the purpose of this study, a structured questionnaire was used to target male and female college students in their 20s representing Generation Z. Generation Z is the generation born between 1996 and 2011, and includes respondents aged 20 to 24 as of 2021, the 20s of Generation Z [17],[18]. Millennials and Generation Z account for a high percentage of live commerce use, so they were included as the main users.

3-2 Sampling and Research Process

After classifying live commerce into two types, an online survey was conducted. The final survey subjects used in this study were 127, and random sampling was performed. As for the survey method, a structured questionnaire was used after the subjects watched a live commerce video, and the questionnaire was directly filled in by self-filling method.

3-3 Production of Experimental Video

Assuming that the para-social interaction effect of live streaming commerce is affected by the degree of involvement, we tried to select products with a certain degree of involvement in the survey subjects. To this end, through a preliminary survey, a list of products with high involvement was first made for 32 college students, and then the laptop product with the highest frequency was selected. The experimental video was composed of about 2 minutes in total, 1 minute in the beginning, 1 minute in the second half, and 1 minute in the middle by editing the previously executed notebook live commerce material (Samsung notebook, 10 minutes and 21 seconds video) (refer to Appendix). Considering the length of the video, a question asking about commerce content was placed in the question item to check the prior understanding of the response content. The degree of involvement and awareness of the experimental image was checked (manipulation check).

3-4 Items

This study referred to previous studies [11] to understand the quasi-social interaction of live commerce. Specifically, 'show host makes friends friendly', 'show host looks natural and honest', 'show host is friendly like someone you've known for a long time', 'have you ever imagined having an intimate conversation with a show host?' Four items were measured on a 7-point scale (very much - not at all) (α = .735).

FoMO (Fear of Missing Out) is a concept derived from external stimulation or internal self-control, and was used by modifying the scale of Friggbilski et al. [19][13] with reference to previous studies. In detail, FoMO includes 'I get anxious when I miss an appointment', 'I get nervous when I can't suddenly go to an appointment with my friends', 'I'm anxious when I can't hear from my friends', 'I feel anxious when others around me Five items of 'it is important to know the brand you use' and 'it is important to buy a product that are popular with others' were measured using a 7-point scale (α = .882).

Involvement refers to the perception of relevance or importance to a product. According to previous studies, consumers attempt to acquire product knowledge when they perceive a high level of involvement with the product. In this study, the items used by Chan-wook Park (2003) were used for involvement in this study, and the items 'products sold in live commerce are important to me' and 'I am interested in products advertised by live commerce' were measured on a 7-point scale. (α = .863).

Advertising attitude is the consumer's favorable or unfavorable feeling toward live commerce advertisement. Using the items of Mackenzie & Lutz (1986), 'I like this live commerce advertisement', 'I am interested in this live commerce advertisement' A total of 3 items (α = .924) of 'I like this live commerce advertisement' and 'I like this live commerce advertisement' were measured on a 7-point scale (very much - not at all).

In order to measure the purchase intention of the product in the future, existing studies (Lee Jun-il and Kim Hyo-seok, 2007) were used to measure 'I want to purchase the product advertised in this live commerce' 'I want to recommend to others' and 'I want to purchase this live commerce advertisement product even later' were measured on a 7-point scale (α = .842).

3-5 Results

In order to confirm the appropriateness of the questionnaire, the reliability coefficient (Cronbach α) was checked by pre-investigating the video material for 32 college students. As a result of measuring the prior awareness (M = 2.34, SD = 1.09) of the experimental object on a 7-point scale, it was judged that contamination by awareness would be small with a recognition level below the average. Product involvement was measured on a 7-point scale using two items: 'This product is important to me' and 'I've always wanted to know information about this product'. (M = 4.19, SD = 1.20) It was confirmed that it was appropriate for the experiment.

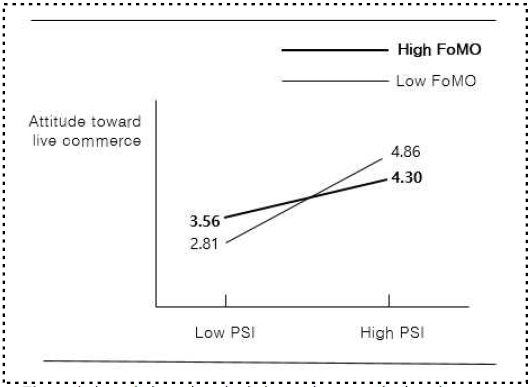

Hypothesis 1 predicted that the effect of the difference in PSI between show host and viewer on the advertising effect (advertising attitude and purchase intention) on live commerce would be different according to the user's internal characteristic factor, FoMO. The PSI group was divided into a low group (67 people) and a high group (60 people) based on the average of 4 items (M = 3.51, SD = 1.09). FoMO was divided into low FoMO (65) and high FoMO (62) based on the median value of 2.82.

As a result of the analysis, as in [Table 1] and [Table 2], PSI and FoMO showed a significant interaction effect (F = 10.441, p < .01).

Specifically, in the low PSI group, the high FoMO group (high FoMO M = 3.56, SD = 1.09) had a higher attitude toward live commerce than the low FoMO M = 2.81, SD = 1.20 group, but in the high PSI group, the FoMO The group with low (low FoMO M = 4.86, SD = 1.08) had a higher attitude toward live commerce than the group with high (high FoMO M = 4.30, SD = 1.00).

In other words, as shown in [Figure 3], when the PSI was low, the group with the high FoMO showed a relatively more positive advertising attitude than the group with the low FoMO. Conversely, when PSI was high, the group with low FoMO showed more positive advertising attitude than the group with high FoMO. This suggests that broadcasting a user's individual FoMO, that is, a broadcast that enhances PSI, that is, communication with a group with low fear of isolation, can increase the positive attitude toward live commerce the most.

Next, as a result of examining the effects of PSI and FoMO on purchase intention according to Hypothesis 1-2, the interaction effect of PSI and FoMO on purchase intention was not significant (F = 1.934, p = .167). Therefore, hypothesis 1-2 was rejected. As to the main effect, the group with high PSI (M = 4.08, SD = 1.19) had a higher purchase intention than the group with low PSI (M = 3.03, SD = 1.66), indicating that PSI had a significant effect on purchase intention. was found to have an effect (F = 14.477, p < .001).

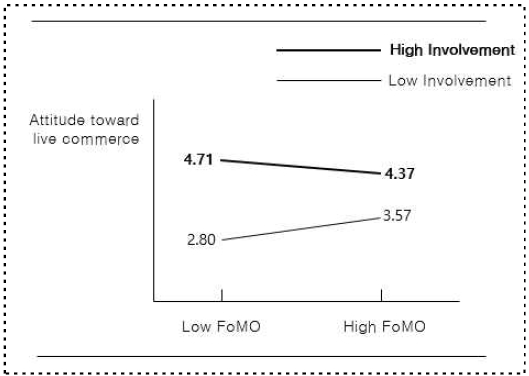

Hypothesis 2 hypothesized that the user's involvement in the product would have an effect on the effect of FoMO on the effectiveness of live streaming commerce. To this end, we divided the low-involvement group (N=69) and high-involvement group (N=58) based on the average level of involvement 3.02 (SD = 1.43), and examined whether there were differences in advertising attitudes and purchase intentions according to FoMO. First, as a result of examining the difference in advertising attitudes according to Hypothesis 2-1, it was found that as shown in [Table 3] and [Table 4], the involvement group had a significant effect on the advertising attitude according to the form (F=7.532, p < . 01).

That is, in the low FoMO group, the difference between the low involvement group and the high involvement group (low involvement M = 2.80, SD = . It was found that the difference between the high groups (low involvement M = 3.57, SD = 1.07 vs. high involvement M = 4.37, SD = .98) was relatively small.

Therefore, in the case of a group with a low FoMO overall, it can be seen that the greater the involvement, the higher the advertising attitude, and the difference according to the involvement can appear larger in the larger FoMO.

This means that advertising a high-involved product for a low-FoMO group may be more positive than for a low-involved product for a high-FoMO group( <Figure 4>).

Meanwhile, as a result of examining the interaction effect of FoMO and involvement on purchase intention, there was no significant interaction effect (F = .054, p = .816). Therefore, hypothesis 2-2 was rejected. Specifically, looking at the main effect, the difference in purchase intention according to the group involved was statistically significant (F = 26. 342, p < .001). Specifically, the average purchase intention of the high-involvement group (M = 4.25, SD = 1.27) was higher than the average purchase intention of the low-involvement group (M = 2.92, SD = 1.49).

IV. Conclusion

4-1 Summary of Results

The purpose of this study is to investigate the role of personal factors such as user's FoMO and product involvement in the process of influencer and content user's PSI on product attitude, purchase intention, and live commerce shopping addiction. The results of the experimental study targeting 127 college students are as follows.

First, it was found that influencers' PSI in live streaming commerce regulates their attitude toward live commerce according to FoMO, which is an internal characteristic factor of consumers. Specifically, in the low PSI group, the group with high FoMO had a higher attitude toward live commerce than the group with low FoMO, but in the high PSI group, the group with low FoMO had a higher attitude toward live commerce than the group with high FoMO.

Second, on the attitude of live streaming commerce, FoMO and user's product involvement showed a statistically significant interaction. In other words, in the high-FoMO group, the difference between groups according to the involvement was relatively small, but in the low-FoMO group, the advertisement attitude toward the high-involvement product was relatively higher than that of the low-involvement, indicating a large difference between the groups according to the involvement.

The implications of this study are as follows.

First, in order to increase the attitude toward live streaming commerce, it is necessary to produce broadcast content considering the PSI level between influencers and users and the individual's fear of isolation, that is, FoMO. For example, it has been shown to moderate attitudes toward live commerce according to Specifically, when targeting a group with a high FoMO, lowering the PSI can increase attitudes, but when targeting a group with a low FoMO, it may be appropriate to increase the PSI further as the fear of isolation or anxiety about social belonging is low.

Second, influencers who produce content to increase their purchase intention in live commerce need to increase their PSI with users (viewers).

Third, as a result of this study, it can be seen that in the case of a group with low FoMO, the greater the involvement, the higher the advertising attitude, and the difference according to the involvement may appear larger in the condition of low FoMO (low fear of isolation). Therefore, in the case of a low FoMO group, advertising a product with a high degree of involvement may be relatively more advantageous.

Recently, as influencer marketing activities increase, there are also voices that the content produced by influencers is excessively commercialized or broadcast unilaterally without considering the viewer's internal characteristics, which can negatively affect the product. Typically, in the shopping process through live commerce, the user's sense of social belonging or desire for participation has increased. Accordingly, there is an increasing argument that it is necessary to appropriately enhance social interaction even in online situations such as social media in consideration of these user characteristics.

In this context, this study focuses on the interaction between users of influencers who produce live commerce, and examines the influence of FoMO and product involvement as an individual's social desire on the live commerce purchase effect process.

As a result of this study, it was found that the influencer's PSI plays a positive role in the attitude toward live commerce according to the user's FoMO characteristics. In other words, it was found that the lower the FoMO group, the more positively they were able to respond to the broadcast that raises the PSI. This means that individual FoMO plays an important moderating role in the persuasion effect process according to influencers' PSI. Also, in practice, these results suggest that PSI should be limited at an appropriate level when reviewers produce review content for commercial purposes or when companies support review content for marketing purposes.

Recently, FoMO of social media users has been shown to be an important social media activity motive, and it is desirable to strengthen PSI with users as a content planner or producer in this regard. This study has some practical implications for planning and producing live commerce contents by examining the advertising effects of recent live commerce in terms of interaction and user needs. Nevertheless, this study has several limitations including the general properties of experimental studies.

4-2 Limitations

As for the limitations of this study, first, the time of the experimental video was greatly reduced in the process of producing the stimulus, so it seems that the naturalness of the process was insufficient compared to the real live streaming commerce. Considering the experimental time, the broadcast is conducted within a short time, so there is a limit to sufficiently containing content that relieves tension or expresses intimacy for the purpose of PSI that an actual YouTube video can have. Second, the study did not control the influence of factors such as reliability, attractiveness, and liking as information source attributes of influencers. In addition, the individual linguistic characteristics variables were not sufficiently controlled. The language proficiency characteristics of live commerce may vary from person to person, and the reliability of broadcast content may vary as a result, so it is necessary to control this. In follow-up studies, it is necessary to examine the overall effect relationship through the structural equation model by controlling exogenous variables or adding various variables including information source attributes and product types.

References

-

K. Ko, “A Study on the Data Service linked to Subtitle Advertisement and its Advertisement Effectiveness”, Journal of Digital Contents Society, Vol. 22, No. 11, pp. 1807-1813, Nov. 2021.

[https://doi.org/10.9728/dcs.2021.22.11.1807]

-

X. DDou, J. A. Walden, S. Lee and J. Y. Lee, “Does source matter? Examining source effects in online product reviews”, Computers in Human Behavior, Vol.28, No.55, pp.1555-1563, Sep. 2012.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.03.015]

-

I. Beyens, E. Frison and S. Eggermont, “I don’t want to miss a thing”: Adolescents’ fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents’ social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook related stress. Computers in Human Behavior, Vol.64, pp.1-8. Nov. 2016.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.083]

-

J. A. Roberts and M. E. David, “The Social media party: fear of missing out (FoMO), social media intensity, connection, and well-being.” International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, Vol.36, No.4, pp.386-392. Jul. 2019.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2019.1646517]

-

De Veirman, Cauberghe and Hudders, “Marketing through Instagram influencers: the impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude”. International journal of advertising, Vol.36, No.5, pp.798-828. Jul. 2017.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1348035]

-

Hughes, Swaminathan, and Brooks, “Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: An empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns”. Journal of Marketing, Vol.83, No.5, pp.78-96. Jun. 2019.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242919854374]

- E. S. Lee, “The Effect of Social Media Influencer’s Parpasocial Interaction and Relationship on Users‘s Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention”. Korea Contents Academy Journal, Vol. 21, No.3, pp.270-281. Mar. 2021.

- T. Park and H. Kim, “18G Typing Or Clicking: the Effect of Typing a Promotion Code on Online Shopping Satisfaction”. ACR North American Advances. 2019.

-

T. Hartmann, and C. Goldhoorn, “Horton and Wohl revisited: Exploring viewers' experience of parasocial interaction”. Journal of communication, Vol. 61, No.6, pp.1104-1121. Dec. 2011.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01595.x]

-

A. P. Schouten, L Janssen and M. Verspaget, “Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in advertising: the role of identification, credibility, and Product-Endorser fit”. International journal of advertising, Vol. 39, No.2, pp.258-281. Jul. 2020.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1634898]

-

S. J., Lennon, M. M. Sanik, & N. F. Stanforth, “Motivations for television shopping: clothing purchase frequency and personal characteristics”. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, Vol. 21, No.2, pp.63-74. Mar. 2003.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0887302X0302100202]

-

J. Reagle, “Following the Joneses: FOMO and conspicuous sociality. First Monday. Vol. 20, No. 10, Oct. 2015.

[https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v20i10.6064]

- E. S. Joo, S. Y. Cheon, and S. J. Shim, “Study on the Validation of the Korean Version of the Fear of Missing Out (K-FoMO) Scale for Korean College Students”. Korea Contents Academy Journal, Vol. 18, No.2, pp.248-261. Feb. 2018.

-

A. E. Dempsey, K. D. O'Brien, M. F. , Tiamiyu, and J. D. Elhai, “Fear of missing out (FoMO) and rumination mediate relations between social anxiety and problematic Facebook use”. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 9, 100150. Jun. 2019.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100150]

-

J. B., Manneville and P. Olson, “Banded convection in rotating fluid spheres and the circulation of the Jovian atmosphere”. Icarus, Vol. 122, No.2, pp.242-250. Aug. 1996.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/icar.1996.0123]

-

R. E., Petty, J. T., Cacioppo and D. Schumann, “Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement”. Journal of consumer research, Vol. 10, No.2, pp.135-146. Sep. 1983.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/208954]

-

S. Rose, and A. Dhandayudham, “Towards an understanding of Internet-based problem shopping behaviour: The concept of online shopping addiction and its proposed predictors”. Journal of behavioral addictions, Vol. 3, No.2, pp.83-89. Feb. 2014.

[https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.3.2014.003]

- J. H. Shin, “Media use of millenial generation and Z generation”. KISDI STAT Report, 19, No.4, pp.2-7. 2019.

-

S. B. MacKenzie, R. J. Lutz and G. E. Belch, “The role of attitude toward the ad as a mediator of advertising effectiveness: A test of competing explanations”. Journal of marketing research, Vol. 23, No.2, pp.130-143. May. 1986.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378602300205]

- https://www.wowza.com/blog/live-commerce-streaming

Appendix

저자소개

1999년 : 연세대학교 대학원 (문학석사)

2009년 : 한양대학교 대학원 (문학박사-광고홍보제작)

1997년~1999년: 상암커뮤니케이션즈

2000년~2002년: 웰커뮤니케이션즈

2006년~현 재: 선문대학교 미디어커뮤니케이션학부 교수

※관심분야 : 브랜디드 콘텐츠(Branded Contents), 광고 크리에이티브 등

2004년 : 한양대학교 일반대학원 (문학석사-광고홍보)

2021년 : 동국대학교 영상대학원 문화콘텐츠학과 박사수료

2005년~2009년: 한국CM전략연구소 책임연구원

2011년: 한남대학교 미디어영상학과 시간강사

2017년: 선문대 미디어커뮤니케이션 시간강사

※관심분야 : 디지털 미디어 콘텐츠, 영상 광고/홍보

2001년 : Iowa State University (M.S)

2007년 : University Of Iowa (Ph.D )

2008년~2010년: 프레인앤리

2011년~현 재: 선문대학교 미디어커뮤니케이션학부 교수

※관심분야 : 기업 PR, 공공캠페인, CSR, 과학커뮤니케이션 등