The Effects of Group Identity and Recommendations on Comment Incivility Perception and Evaluation: Focusing on the Difference Between American Democrats and Republicans

Copyright ⓒ 2019 The Digital Contents Society

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-CommercialLicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

A 2x2 online experimental study was employed to examine the effects of American participants’ group identity (in-group vs. out-group) and how the presence of social influence via recommendations (recommendations vs. no recommendations) influenced their perceptions of uncivil comments and evaluation of commenters who posted uncivil comments. More importantly, the study examined how participants’ responses to incivility differed between American Democrats and Republicans. Three-way ANOVA analyses were conducted to understand the effects of group identity, recommendations, and partisanship as well as the interaction effects. Results showed that both Democrats and Republicans were highly influenced by the presence of recommendations but with response patterns that differed significantly. Implications of findings for academia as well as society are discussed.

초록

본 연구에서는 2x2 온라인 실험을 통해서 개인의 집단 정체성 (동일집단 vs. 타집단)과 악성댓글에 달린 추천 표시 (유 vs. 무) 에 따라 미국 인터넷 사용자들의 악성댓글 인지와 악성댓글 작성자의 판단의 변화를 실험을 통해 실증적으로 분석하였다. 나아가 이러한 반응들이 미국 정치적 정당 (민주당 vs. 공화당) 에 따라 어떠한 차이를 나타내는지 역시 살펴보았다. 삼원분산분석을 실시한 결과, 악성댓글 작성자를 판단함에 있어서 개인의 집단 정체성, 댓글 추천의 유무 그리고 정당성이 강한 상호작용을 일으키고 있음을 발견하였다. 특히 악성댓글에 추천이 달렸을 경우, 민주당과 공화당의 악성댓글 작성자 판단에 큰 차이가 있음을 발견할 수 있었다. 본문에서는 위와 같은 결과들의 학문적 그리고 사회적 의미에 대해서 더욱 구체적으로 논의하였다.

Keywords:

American Partisanship, Recommendations, Social Identity, Uncivil Comment키워드:

집단 정체성, 댓글 추천, 악성댓글, 미국 정당 정체성Ⅰ. Introduction

While scholars have observed the decline in political polarization at the elite level[1], uncivil discussions among people continue to persist[2]. Referred to as uncivil uses of language and manner of expression, incivility is widespread, especially in online communication[3]. Scholars have found that uncivil discussions easily lead to intense flaming and acrimonious debates[4]. Incivility online interferes with users’ ability to engage in productive discussions on the internet.

Online uncivil comments are well-documented around controversial political issues that often encourage incivility based on partisan identity. Known for its power to bond users who share the same partisan identity and to encourage favoritism for their own group (in-group) over others (out-group) partisan identity often incites incivility in conflicts between opposing groups [5],[6]. Moreover, incivility between partisan groups is regarded as a strong predictor of deepening polarizations [7],[8].

Although partisan identity in incivility research is well-established, the literature on incivility has rarely examined whether different partisan groups, for example, Republicans and Democrats, show different patterns of responses when exposed to uncivil comments online. Traditionally, Conservatives and Liberals are known to have different sets of values[9], moral[10], personalities[11] and opinions that create a unique partisan characteristics and responses for each group. Thus, it is logical to expect that two partisans may show distinctive patterns of responses, thereby influencing the area of incivility differently.

The aim of this study is to expand the literature of incivility by examining whether current findings of incivility research may apply to these distinctively partisan groups of American Democrats and American Republicans. Based on an online experiment, the current study attempts to examine not only how Democrats and Republicans respond to uncivil comments but also whether partisan responses are influenced by an environment where the public is explicitly involved in uncivil communication situations via social recommendations such as “recommendations.”

Ⅱ. Theoretical Discussion

2-1 Uncivil Comments and Social Identity

Incivility, as mentioned above, is a form of impolite expression that is commonly considered unacceptable to a society[2]. Online environments, in particular, offer a variety of methods for expression that can include emoticons and images as well as capital letters, expanding the spectrum of incivility. Sobeiraj and Berry (2011) found that uncivil expressions are extensive in terms of its forms [12], making it particularly difficult to define online incivility. Yet, the efforts continue to categorize uncivil comments[12],[13]. Nevertheless, many scholars have observed that uncivil conversations take place often in the area of politics [5],[6].

In the field of politics, one’s partisanship is often identified as the primary factor that divides people into political groups that compete like teams, thus encouraging uncivil discussions[5],[6]. Social identity theory helps to explain how someone’s partisan identity often becomes the primary motivation for uncivil expressions against the other “team” (out-group). Tajifel defined social identity as ‘‘part of an individual's self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership(p.63)“[14]. Strong attachment to a social group, such as partisanship, often leads people to engage in group-differentiation whereby individuals develop “group-thinking” mechanisms (us vs. them). Intergroup differentiation is found to focus on in-group favoritism and out-group derogation[15] with the goal of insuring a positive self-concept for individual members.

The tendency to favor one’s in-group over other groups, referred to as in-group favoritism, is a widely practiced phenomenon. Incivility studies have found that people employ a double standard when identifying and evaluating incivility based on perceptions of whether the uncivil expressions are made by those who do or do not share their own partisan identity[16],[17]. For example, the study conducted by Kim (2018) found that individuals exhibited a more lenient attitude in perceiving incivility when uncivil comments were made by partisans they associated with, while exhibiting less tolerance towards incivility expressed by other partisan group members[16].

One’s group identity also influences how individuals judge uncivil commenters, particularly via out-group derogation, which is used to degrade out-group members. This tendency of out-group derogation has been found to influence how individuals think about another person who expresses an opinion in an uncivil manner. In the same study, Kim (2018) found that individuals will often protect an uncivil commenter in their own party by evaluating more harshly an uncivil comment made by an out-group member even if the level of expressed incivility is similar[16]. In fact, such out-group derogation was found to be greater among those who possess stronger in-group identity[18]. Both in-group favoritism and out-group derogation influence how incivility is evaluated based on political identity.

2-2 Partisanship and Social Influence Online

An extensive amount of research has found that conservatives and liberals have different sets of values[9], morals[10], and personalities[11]. One of the most consistent findings is that conservatives generally put more emphasis on social conformity than liberals[19],[20]. In particular, a study finds conservatives’ conscientiousness personality trait is closely associated their desire to conform to social norm[21]. Similarly, Jost and colleagues found that conservatives have higher scores on conformity and obedience scales compared to liberals[19]. Even across 16 different countries, research has documented the value of conformity to be a strong predictor for political conservativism[20].

In particular, the tendency to conform to social norms among conservatives can be heightened when the norms are aligned with conservatives’ value system. According to the Moral Foundation Theory, conservatives have consistently shown a stronger emphasis on in-group loyalty compared to liberals[10],[22]. When given a hypothetical conflicting moral situation, a recent study found a significant relationship between in-group loyalty and reluctance to violate in-group norms to be more frequent among conservatives than liberals[22]. Taken together, results of these studies support the strength of political ideologies in shaping individuals’ political decisions and actions.

Considering that incivility is an expression that is socially unacceptable, the conservatives’ emphasis on conformity and in-group loyalty may be particularly relevant in Republicans’ perceptions of uncivil comments as well as their evaluations of uncivil commenters. Although political ideologies and political partisanship are not the same, numerous studies have found the two are positively correlated and that the correlations have increased over the past several decades[23]. Thus, the current study expects the similar relationship will likely be expressed differently by Republicans and Democrats.

Especially, in online communication environments where evaluations by other users are immediately known through interactive features such as “like” and “recommend,” the current study expects that Republicans and Democrats will respond differently to incivility. Many studies have found that these features have a major impact on people’s opinions and behaviors by serving as a source for encouraging accuracy as well as for social influence[8],[24-26]. In a recent study, Kim and Park found the presence of recommendations on uncivil comments led other users to perceive the comment board to be so highly polarized that they, too, became less open-minded and ultimately less engaged in discussions[8]. Since studies have shown that social norms are often a stronger determinant of behavior for conservatives than for liberals[19], the presence of recommendations may function as a form of social influence that affects people’s perceptions and evaluations of incivility, particularly among Republicans, who emphasize conformity and in-group loyalty in contrast to Democrats who place lower value on these criteria.

To date, a limited number of studies have tested this assumption within a context where there exists an interaction between group identity and incivility. Moreover, research has not yet empirically tested potential differences that may arise between Republicans and Democrats. In that sense, this study attempts to provide preliminary results by examining how the presence of recommendations may moderate the effects of group identity and how these factors may interact to influence how Republicans and Democrats respond differently to online incivility. Based on that line of reasoning, the current study proposes the following hypotheses and research questions:

H1a: Republicans will perceive in-group (Republican) uncivil comments to be less uncivil when the uncivil comments receive recommendations than when they do not.

H1b: Republicans will perceive out-group (Democrat) uncivil comments to be less uncivil when the uncivil comments receive recommendations than when they do not.

RQ1: Will there be a significant difference in Democrats’ perception of uncivil comments based on the interaction between (a) group identity and (b) whether the uncivil comments receive recommendations or not?

H2a: Republicans will evaluate in-group (Republican) uncivil commenters more favorably when uncivil comments receive recommendations than when they do not.

H2b: Republicans will evaluate out-group (Democrat) uncivil commenters more favorably when uncivil comments receive recommendations than when they do not.

RQ2: Will there be a significant difference in Democrats’ perception of uncivil commenters based on the interaction between (a) group identity and (b) whether the uncivil comments receive recommendations or not?

III. Method

Originally, this study was a 2 (Group Identity: In-group vs. Out-group) x 2 (Recommendations: Yes vs. No) mixed-design online experiment where participants were asked to read three news articles on gun control, abortion, and climate change. For this article, only responses to the news article on gun control are presented. Group identity and the presence of recommendations were used as the independent variables while incivility perception in uncivil comments and evaluation of uncivil commenters were outcomes.

3-1 Participants

For a month-long period in 2015, participants above the age of 18 were recruited from Mechanical Turk (MTurk), a crowd-sourcing system for recruiting volunteer participants to complete small tasks such as surveys for monetary compensation. MTurk has been used by various social scientists to conduct research, in particular, experimental studies[6],[8]. A total of 417 subjects completed the study (211 Democrats vs. 206 Republicans). While three responses were missing, the sample characteristics were: (gender (47.3% male, 52.7% female); age 18-34, 56.8%; 35-74, 43.2%); ethnicity (73.7% White, 8.9% Black or African American, 5.8% Hispanic or Latino, 8.7% Asian or Asian-American, 2.9% others); education (84.5% Bachelor's degree or below, 15.5% Some graduate education including professional certificates or above).

3-2 Design and Procedure

When participants entered the online experiments through links sent via Qualtrics, a survey software application, participants were first asked about their partisanship. Based on their partisanship responses, Qualtrics randomly assigned participants to one of four conditions where the top comment under a news article on gun control was manipulated to represent either the same partisanship (in-group) or other partisan identity (out-group) of the partisanship. The comment was further manipulated to have recommendations or not: (1) uncivil in-group with recommendations, (2) uncivil in-group without recommendations, (3) uncivil out-group with recommendations, and (4) uncivil out-group without recommendations.

Once assigned to a condition, participants were asked to read a neutral tone of 200-word news article on the issue of gun control with four comments written below. Across four conditions, the same news article on the issue of gun control was given to all participants. In all four conditions, the first comment on the top was represented as uncivil (see Table 1) while the rest of following three comments were civilized expressions. After reading the article with comments, participants were asked to answer a post-manipulation questionnaire and were financially compensated ($1) via their Amazon account when they finished.

3-3 Manipulation

The first commenter's partisanship was matched with participants’ partisanship to represent either (a) the same as that of the respondent (in-group) or b) the partisanship that differed from that of the respondent’s (out-group). First, the partisanship of participants was identified by adding responses from two questions: Participants were first asked to indicate their party identification: “What is your party identity?” (1=Democrat, 2 = Republican, 3= Independent, 4= Others, 5= None). Respondents who did not identify with a party either as a Democrat or Republican previously were asked a follow-up question to indicate on 7-point scale their political leaning toward either party: “While you may not identify yourself as a partisan, do you think you lean toward one of the two parties?” (1= “leaning toward Democratic Party” to 7= “leaning toward Republican Party” with 4= “no leaning toward Democratic or Republican party). The partisan leaning was recoded to indicate either Democrat (1-3) or Republican (5-7). People who showed no leaning toward either Democratic or Republican Party were eliminated from the study. The first and the second questions were combined to indicate the respondents’ partisan identity (Democrats: 50.6%; Republican: 49.4%). Then, participants’ perception of the first commenter’s party identity (1=Democrat, 2 = Republican, 3= Independent, 4= Others, 5= None) was asked to make match for either a) in-group or b) out-group assignment. The Chi-square showed that group assignment was successful (χ2=287.213, df=1, P<.001). The first comment was further manipulated to have either recommendations (189-201) or no recommendations. Respondents were asked to rate the volume of recommendations on the first manipulated comment from none to a lot. Those who did not answer the question were removed from the analysis. The other three civil comments in each condition received recommendations ranging from 5 to 60 on each comment. Again, the result of the t-test showed the recommendations was successfully manipulated (t= -34.181, df=322.744, P<.001).

3-3 Dependent Variables

1) Comment Incivility: Three questions were asked and then added to generate a measure for the level of incivility that participants perceived from the first comment: The comment(s) expressed by Democrats/Republicans were (a) inappropriate, (b) offensive, and (c) uncivil. All items were assessed using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from (1)strongly disagree to (7)strongly agree. (α = .932, M = 14.28, SD = 5.20).

2) Evaluation of the Commenter: Three questions were asked to create a measure for the participants’ favorability toward the commenter, as employed by Marques and his colleagues[27]: What is your impression of the commenter? ranging from (1= very unfavorable to 7= very favorable), (1= very disrespectful to 7= very respectful), and (1= very bad example to 7= very good example)(α = .959, M= 8.71, SD=5.48).

Ⅳ. Results

To examine the research questions and hypotheses, 2 (Group Identity: In-group vs. Out-group) x 2 (Recommendations: Yes vs. No) x 2 (Partisanship: Democrats vs. Republican) Analyses of Variance (ANOVA) were performed.

A three-way ANOVA revealed that group identity (F (1, 417)=29.58, ηp2=.067 p <.001) and partisanship (F (1, 417) =4.24, ηp2=.010, p<.05) influenced individuals’ judgment in perceiving comment incivility (see Table 2). In particular, Democrats perceived less incivility in comments (M=13.83, SD=5.32) than Republicans (M=14.70, SD=5.09). Furthermore, a marginally significant three-way interaction among the presence of recommendations, group identity, and partisanship was found (F (1, 417)=3.83, ηp2=.009, p=.05). Although marginally significant, it was found that Republicans perceived in-group uncivil comments to be less uncivil when the uncivil comments received recommendations (M=13.00, SD=4.85) than when they did not (M=13.75, SD=5.34). On the other hand, Republicans perceived out-group uncivil comments to be less uncivil when they did not received recommendations (M=15.95, SD=4.63) than when they did (M=16.78, SD=4.52). Therefore, H1a and H1b was not supported.

TAgain, though marginally significant, the difference was found for Democrat’s perception of uncivil comments based on an interaction between (a) group identity (in-group vs. out-group) and b) whether the uncivil received recommendaton or not. For Democrats, results showed that in-group uncivil comments were perceived as being more uncivil when the comments received recommendations (M=13.02, SD=5.37) than when there were no recommendations (M=12.25, SD=5.09). However, Democrats perceived out-group uncivil comments to be more uncivil when they did not receive recommendations (M=15.83, SD=4.66) than when they did (M=14.28, SD=5.53).

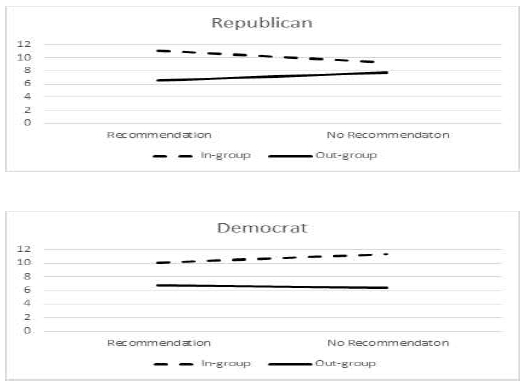

A three-way ANOVA revealed a significant three-way interaction among the presence of recommendations, group identity, and partisanship in assessing the uncivil commenters (F (1, 417=5.120, ηp2=0.12, p <.05) (see Table 3). The analysis indicated that Democrats and Republicans evaluated uncivil commenters differently based on the participants’ group identity and the presence of recommendations (Figure 1). It was found that Republicans assessed in-group uncivil commenters better when the comments received recommendations (M=11.02, SD=5.42) than when they did not (M=9.25, SD=5.37) while assessing the out-group uncivil commenter less favorably when they received recommendations (M=6.55, SD=5.54) than when they did not (M=7.73, SD=5.53). Therefore, H2a was supported but not H2b.

The significant difference was also found for Democrat’s evaluation of uncivil commenters based on an interaction between (a) group identity (in-group vs. out-group) and b) whether the uncivil comments receive recommendations or not. For Democrats, the in-group uncivil commenter who received recommendations was evaluated less favorably (M=10.11, SD=5.29) than when no recommendations were received (M=11.40, SD=5.14). On the other hand, Democrats assessed out-group uncivil commenters more favorably when they received recommendations (M=6.74, SD=4.76) than when there were no recommendations (M= 6.35, SD=4.09).

Ⅴ. Conclusion

Congruent with previous findings[5],[16], the effects of a match between participants’ group identity with the uncivil commenter’s group identity were influential in perceiving the level of incivility as well as assessment of the uncivil commenters. As for the interaction effect, the results showed only a marginally significant interaction effect among group identity, recommendations, and partisanship for the perception of inciviltiy. Republicans showed more lenient attitudes towards comment incivility when an in-group uncivil comment received recommendations as compared to Democrats who were less tolerant towards incivility when the uncivil comment made by an ingroup member received recommendations. In the meantime, results showed a strong significant interaction effect among group identity, recommendations, and partisanship for the evaluation of commenters.

Republicans evaluated their party’s uncivil commenter more favorably when the uncivil comment received recommendations yet assessed an out-group’s uncivil commenter more harshly when the uncivil commenter received recommendations. Within the broader realm of social conformity, the Republicans’ tendency to support in-group may be understood as a form of powerful normative influence of the majority. That is, the recommendations on uncivil comments in this study may have functioned as a source for setting group norms online or at least social approval within that particular online community. In turn, recommendations may have led Republican participants to believe that the level of incivility within that particular online environment was acceptable, supporting the previous finding that Republicans are highly associated with social conformity and that the effects of social influence are especially relevant for Republicans[23], [24].

On the other hand, the current study found that the witnessing of recommendations in response to in-group uncivil comments led Democratic participants to be more critical in judging the uncivil commenters. Democrats evaluated their party’s uncivil commenter less favorably when the comment received recommendations. What is particularly intriguing is that Democrats evaluated their in-group uncivil members more harshly than out-group uncivil members when recommendations were present. Instead of taking the recommendations as social approval, Democrats may have viewed the approvals as potentially harming the good image of their group. This finding supports previous findings of the black sheep effect that happens when individuals tend to derogate their own group members for their misdeeds to save the group’s positive reputation[27]. Future research should further explore the dynamics of different combinations of partisanship, incivility, and online presence of audience in greater detail.

As with many other experimental studies, this research suffers from external validity that is attributed to the experiment methodology[28]. In particular, the low external validity of the group identity representation used in these studies should be mentioned, though the use of the partisan icon to represent one’s group identity takes place in reality. Moreover, the generalizability of the results from these studies should be cautiously considered as the studies cover only one type of uncivil comment along with only one type of social recommendation used in this study. Future research should continue to explore other levels and types of uncivil comments as well as other types of interactive features that are not covered in the current study but widely used online.

Despite the limitations, the findings of this study contribute to not only academic research but also to society. Academically, the findings provide further support for previous studies indicating how Democrats and Republicans behave differently in the context of online incivility. In doing so, the findings of this study go beyond the context of incivility and partisanship, suggesting the necessity to study the effects of the social influence, especially social influence online, as observed in various situations with different groups of subjects. As for society, the findings may lead to a better understanding of how to deal with incivility that occurs between Republicans and Democrats, especially using everyday tools such as social recommendations. Eventually, social recommendations and similar tools may exert social pressure that may tone down rampant online incivility so that users are able to conduct thoughtful discussions about a range of topics.

Acknowledgments

이 연구는 2019학년도 단국대학교 대학연구비 지원으로 연구되었음을 밝히며, 지원해 주심을 감사드립니다.

본 연구의 일부 내용은 제1저자의 학위논문의 일부를 발췌하여 재구성하였음

References

- M. P. Fiorina, Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America, New York, NY: Pearson Longman, 2005.

- S. Herbst, Rude democracy: Civility and incivility in American politics, Philadelphia, PA:Temple University Press, 2010.

-

P. Borah, “Interactions of news frames and incivility in the political blogosphere: Examining perceptual outcomes,” Political Communication, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 456-473, 2013.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2012.737426]

-

Z. Papacharissi, “Democracy online: Civility, politeness, and the democratic potential of online political discussion groups,” New Media & Society, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp.259-283, 2004.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444804041444]

-

B. T. Gervais, “Incivility Online: Affective and Behavioral Reactions to Uncivil Political Posts in a Web-Based Experiment,” Journal of Information Technology & Politics, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp.167–185, 2015.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2014.997416]

-

M. G. Chen and S. Lu, “Online political discourse: Exploring differences in effects of civil and uncivil disagreement in news website comments,” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, Vol. 61, No. 1, pp. 108-125, 2017.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2016.1273922]

-

P. Borah, “Does it matter where you read the news story? Interaction of incivility and news frames in the political blogosphere,” Communication Research, Vol. 41, No. 6, pp. 809-827, 2014.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212449353]

-

J. W. Kim and S. Park, “How perceptions of incivility and social endorsement in online comments (Dis) encourage engagements,” Behaviour & Information Technology, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 217-229, 2019.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1523464]

-

S. H. Schwartz, “Universalism values and the inclusiveness of our moral universe,” Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, Vol. 38, No. 6, pp. 711-728, 2007.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022107308992]

-

J. Graham, J. Haidt and B.A. Nosek, “Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 96, No. 5, pp. 1029-1046, 2009.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015141]

-

K. D. Sweetser, “Partisan personality: The psychological differences between Democrats and Republicans, and independents somewhere in between,” American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 58, No. 9, pp. 1183-1194, 2014.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213506215]

-

S. Sobieraj and J.M. Berry, “From incivility to outrage: Political discourse in blogs, talk radio, and cable news,” Political Communication, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 19-41, 2011.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2010.542360]

-

J.W. Kim, H.I. Jo and B. G. Lee, “ A Comparison Study on Performance of Malicious Comment Classification Models Applied with Artificial Neural Network,” Journal of Digital Contents Society, Vol. 20, No. 7, pp. 1429-1437, 2019.

[https://doi.org/10.9728/dcs.2019.20.7.1429]

- H. Tajfel, Social categorizations, social identity, and social comparison. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations, London: Academic Press, pp. 61–76, 1978.

- M. B. Brewer and R.J. Brown, Intergroup Relations. In Gilbert, D. T., Fiske, S.T., & Gardner, L., (Eds.) Handbook of Social Psychology, Boston, Mass.: McGraw-Hill, Vol 2, pp. 554–594, 1988.

-

J. W. Kim, “Online incivility in comment boards: Partisanship matters-But what I think matters more,” Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 85, pp. 405-412, 2018.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.015]

-

N. M. Lozano-Reich and D. L. Cloud, “The uncivil tongue: Invitational rhetoric and the problem of inequality,” Western Journal of Communication, Vol. 73, pp. 220-226, 2009.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10570310902856105]

-

T. Postmes, R. Spears, N. R. Branscombe and H. Young, “Comparative processes in personal and group judgments: Resolving the discrepancy,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 76, pp. 320-338, 1999.

[https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.76.2.320]

-

J. T. Jost, B. A. Nosek and S. D. Gosling, “Ideology: Its Resurgence in Social, Personality, and Political Psychology.” Perspectives on Psychological Science, Vol. 3, pp. 126-136, 2008.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00070.x]

-

Y. Piurko, S. H. Schwartz and E. Davidov, “Basic personal values and the meaning of left-right political orientations in 20 countries,” Political Psychology, Vol.32, pp. 537-561, 2011.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2011.00828.x]

-

A. S. Gerber, G. A. Huber, D. Doherty and C. M. Dowling, “The big five personality traits in the political arena,” Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 14, pp. 265–287, 2011.

[https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051010-111659]

-

S. van der Linden and C. Panagopoulos, “The O’Reilly factor: An ideological bias in judgments about sexual harassment,” Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 139, pp. 198-201, 2019.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.022]

- G. Jacobson and J. Carson, The Politics of Congressional Elections. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2015.

-

S. Senecal and J. Nantel, “The influence of online product recommendations on consumers’ online choices,” Journal of Retailing, Vol. 80, No. 2, pp.159-169, 2004.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2004.04.001]

-

S. Messing and S. J Westwood, "Selective exposure in the age of social media: Endorsements trump partisan source affiliation when selecting news online," Communication Research, Vol. 41, No. 8, pp. 1042-1063, 2014.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212466406]

-

S. Kim and D. Shin, “The effect of Empathy in Eye vision to users in Facebook using an Eye Tracker,” Journal of Digital Contents Society, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 387-393, 2019.

[https://doi.org/10.9728/dcs.2014.15.3.387]

-

J. M. Marques and D. Paez, The black sheep effect: Social categorization, rejection of ingroup deviates, and perception of group variability. In W. Stroebe, & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European review of social psychology, Chichester, U&K: Wiley. pp. 37-68, 1994.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779543000011]

- R. E. Kirk. (1995). Experimental Design: Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences. CA. Wadsworth.

2016년 : The University of Texas at Austin (저널리즘 박사)

2019년~현재: 단국대학교 커뮤니케이션학부 조교수

※관심분야:디지털 저널리즘 (Digital Journalism), 디지털 커뮤니케이션 (Digital Communication) 등